Diagrams of Theory: Douglas and Wildavsky's Grid/Group Typology of Worldviews

For roughly two years, I was obsessed with risk. Naturally, this quickly led to the work of Mary Douglas and Aaron Wildavsky. The former more so than the latter. (It was coincidental that one of her former research assistants at Northwestern was my theory professor during this same period of risk-obsession.)

Douglas received her PhD from Oxford in 1952 after completing fieldwork in the Belgian Congo (in what would become the Democratic Republic of the Congo) from 1949-1951, and returning in 1953. Her first book based on this ethnographic research was The Lele of the Kasai (1963), which described the matrilineal Lele people. Three years later she would publish her most celebrated book, Purity and Danger, in which Douglas elaborated the ways in which no classification system is exhaustive, and therefore in every culture, there are always anomalies (i.e. “matter out of place”) toward which people feel disgust or fear.

Douglas came of age as an anthropologist during the “crisis of anthropology.” During which the discipline began to accept that the “ethnographic object” was far less bounded than classical ethnographies presented. In other words, anthropology was losing the literal and figurative “islands” into which the foreign (i.e. Western) ethnographer could penetrate, and more anthropologists were beginning to study the west (an academic movement sometimes referred to as “Bringing it back home.”) As a result, Douglas saw that the future of anthropology was “comparative,” which would require some theoretical mechanism by which to compare different societies. It was this concern that inspired what would become the Grid-Group framework and Cultural Theory.

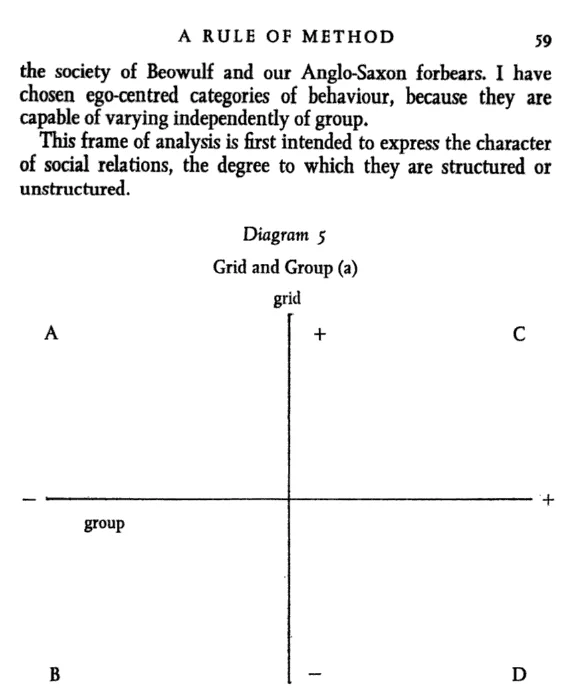

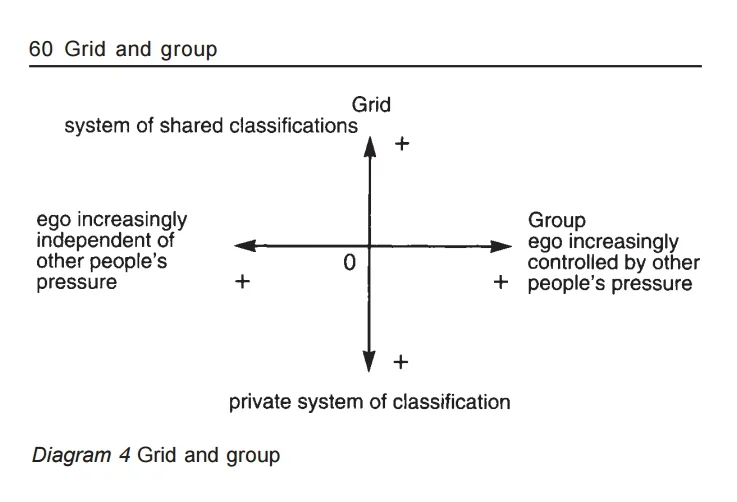

The first iteration of the grid-group diagram (that I could find) is in Douglas’ 1970 book Natural Symbols: Explorations in Cosmology. In the preface to the 1996 edition of this book, Douglas describes Natural Symbols as the follow-up to Purity and Danger. (She also states that, “the diagrams I used seem very complicated now.” [1996:xi]). Shortly after Purity and Danger, Douglas notes that she had extensive conversations with British sociologist Basil Bernstein whom she first met in 1965. Specifically, he challenged her on the idea that classifications matter the same in every society. Maybe there were some who didn’t care about “matter out of place,” and others who would kill because of it.

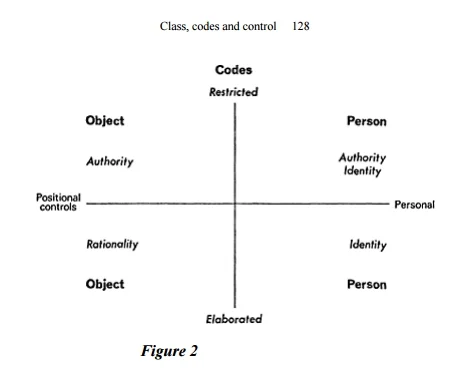

She described his 1965 essay “A socio-linguistic approach to social learning,” later reprinted in Bernstein’s classic Class, Codes, and Control (1971), as having “had an electrifying effect on me_._” This essay was the continuation of ideas he started to elaborate in a 1959 article, “Some sub-cultural determinants of learning; with special reference to language” published in Kölner Zeitshrift für Soziologie und Sozialpsychologie (Cologne Journal of Sociology and Social Psychology) and an empirical analysis, “Language and social class,” published in 1960 in the British Journal of Sociology.

In sum, Bernstein had struck on the idea that an individual’s speech style differed between socio-economic classes as a result of the different social relations within classes. This would come to be known as the “restricted” and “elaborated” linguistic codes used by lower and middle classes, respectively. His work was novel for many reasons, one of which was that sociology at the time had largely overlooked language.

He explains the above (Bernstein 1973:44-45):

The diagram should be read as follows. The vertical and horizontal axes are scaled in terms of the emphasis upon language. The vertical axis refers to degrees of reflexiveness in socialization into relationships with persons and the horizontal axis refers to degrees of autonomy in the acquisition of skills.

Bernstein’s diagram inspired the original version of the grid-group diagram. The above diagrams are taken from the 1971 volume 1 and the 1973 volume 2 (subtitled “Applied studies towards a sociology of language”). They bear a resemblance with Douglas’ diagram from 1970, an influence she explicitly acknowledges throughout Natural Symbols. The more elaborate Bernstein-diagram (above) first appeared in a 1969 article written by Bernstein with Dorothy Henderson titled “Social class differences in the relevance of language to socialization.”

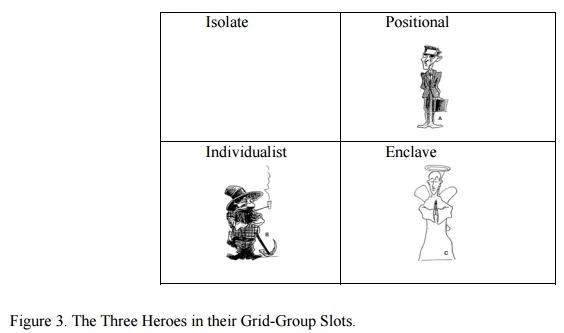

“The smug pioneer with his pickaxe, the stern bureaucrat with his briefcase, the holy man with his halo, they exemplify Max Weber’s three types of rationality: bureaucracy, market, and religious charisma; at the same time as three of the grid-group cultures, positional, individualist, and sectarian enclave.”

This is an excerpt from a course taught by Douglas at the Semiotics Institute Online, “A Course on Cultural Theory: The Group / Grid Model.”

Building on the idea of how best to classify different societies (for comparative analysis), Douglas started by borrowing Bernstein’s two-dimensional classification of family organization – which he refereed to as “positional” and “personal.” She was hoping to connect variation in family organization (which she understood as the social-structural dimension) to variation in emphasis on classification (which she took as the cultural dimension).

Douglas’ theory was also influenced by major global events in the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s. The threat of nuclear war, the environmental movement, anti-war protests, and more. In fact, underlying her work is always a “conservative” tendency that sees the demands of student protests in the West as not just utopian but dangerous.

In 1977, Douglas joined Aaron Wildavsky when he became president of the Russell Sage Foundation to lead the culture section. Wildavsky was specifically curious about the sudden disgust toward the use of nuclear power, which was previously celebrated by the public. They proposed to respond to the overly psychological theories of risk perception with a culturally-attuned theoretical tool that could also be used for policy analysis. In New York in 1978, The Foundation pushed Wildavsky and Douglas’ agenda forward by hosting the “Conference on Grid and Group,” organized by the anthropologist David Ostrander.

In 1979, a major contributor to the theory and student of Douglas at University College, London, Steve Rayner, wrote his PhD dissertation using Grid/Group analysis entitled “The Classification and Dynamics of Sectarian Forms of Political Organization: Grid/Group Perspectives on the Far Left in Britain.”

In 1982, combining the work of students at UCL and those at the Foundation, Douglas edited the volume Essays in the Sociology of Perception, which included several empirical uses of Grid/Group Analysis. Below is the table of contents, which includes numerous empirical settings and many of the second generation of Grid/Group evangelists.

The most clearly articulated version of Grid/Group analysis and what would become known as the “Cultural Theory of Risk,” in Douglas and Wildavsky’s 1982 publication: Risk and Culture: An Essay on the Selection of Technical and Environmental Dangers.

Another vendetta of Douglas’s was vindicating the “primitives.” The notion that “we moderns” were not all that different from our “barbaric” and “uneducated” ancestors. In addition to the dismantling of land boundaries, anthropology was also slowly dismantling the boundary between “us” and “them.” In Risk and Culture, Douglas and Wildavsky argued that despite the spread of the scientific method and rationality in “modern” society, selection of danger and allocation of blame was still a highly politicized process, just as it had been “in the past.”

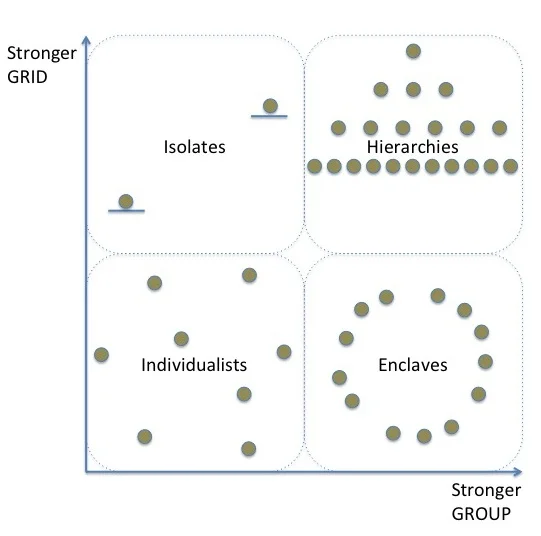

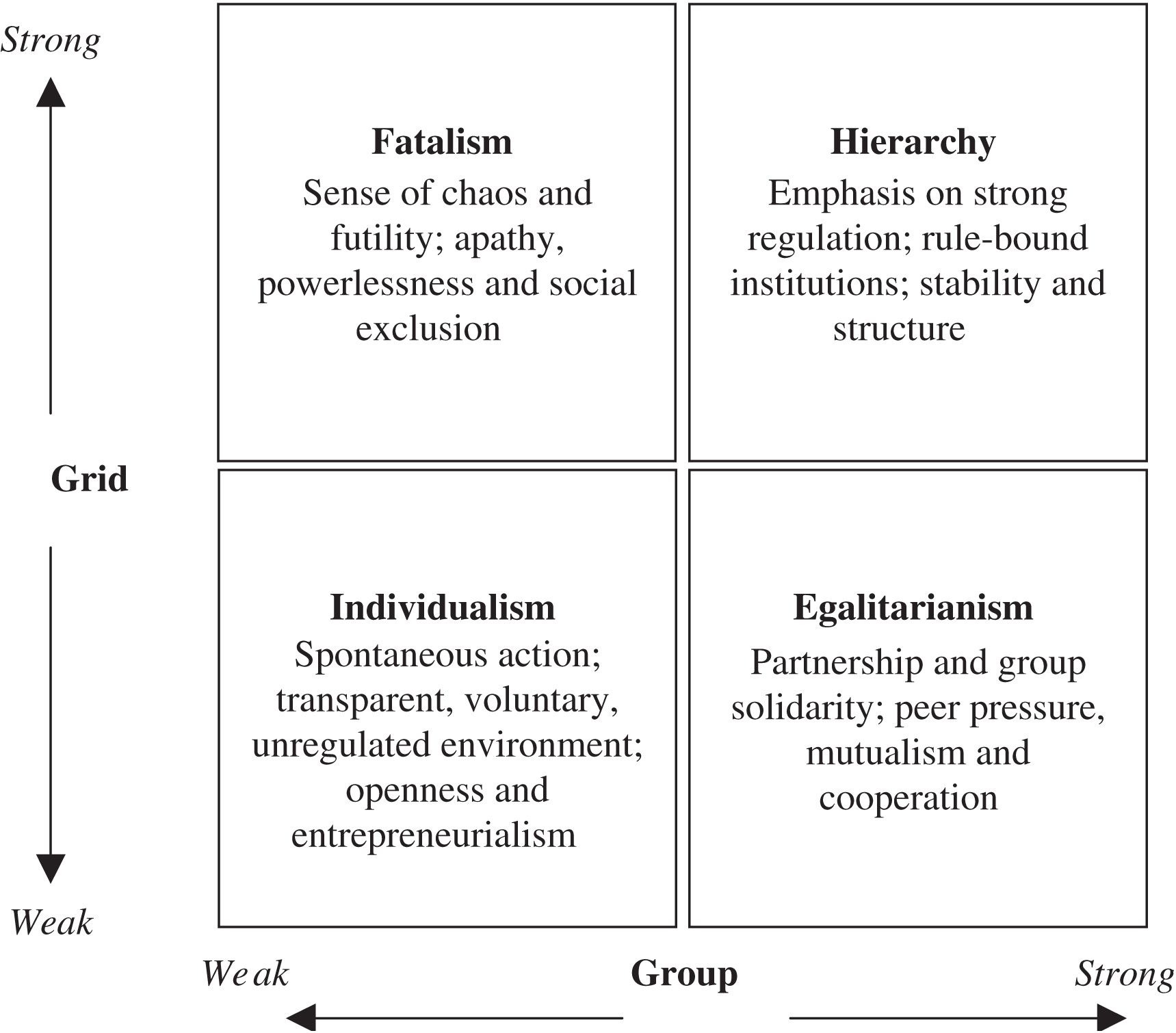

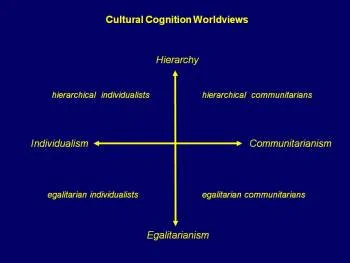

Applying the theory to the selection of danger and dealing out of blame, Douglas and colleagues developed a simple heuristic model which accounts for variations among the social organization of groups within societies (not just between). Across time, space and subculture, they argued that social organization can be categorized into four “world views,” which have important societal correlates, or so the theory goes.

.")

In a 1990 Wildavsky collaborated with Micheal Thompson and Richard Ellis on a textbook titled Cultural Theory - at this point the name Grid/Group theory was changed to “Cultural Theory” (with capital letters required).

In latter renditions of the theory, grid is the level of differentiation of activities and authority; group is the level that people identify with each other (for a comparison of 13 attempts to define “grid” and “group” see an appendix in Oldroyd’s “Grid/Group Analysis for Historians of Science?”). In the former you have labor specialization (or not) and rigid hierarchy (or not). In the latter you have, either, strong communal identity or fragmented individualism.

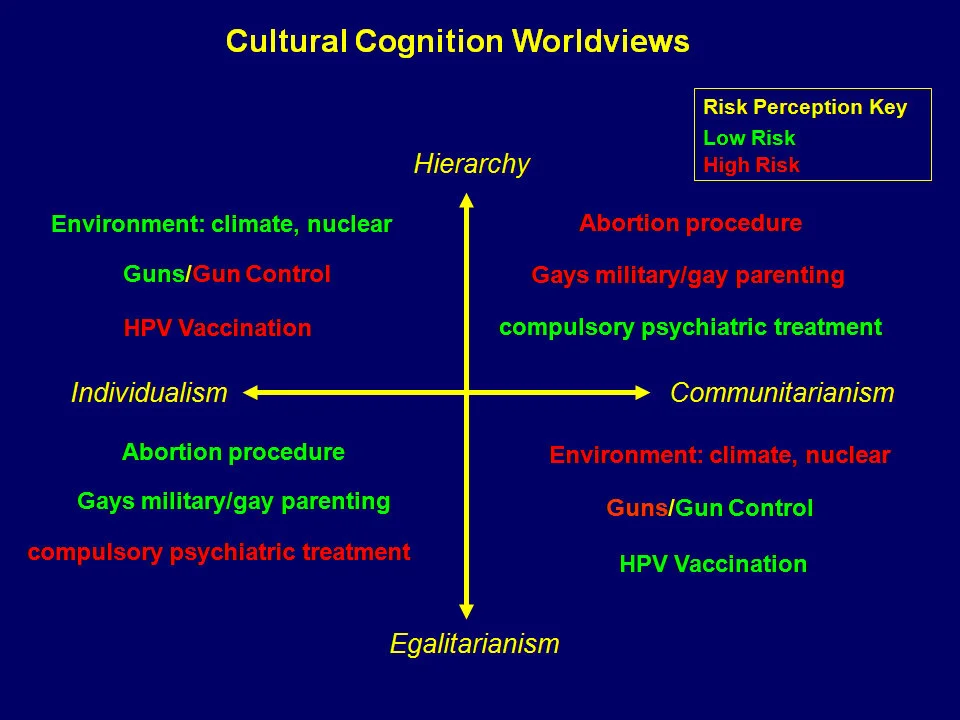

Social and political actors derived their assumptions about appropriate plans of action in the face of various dangers by relying on these - often implicit - “cultural biases.” Thus, Grid/Group analysis can be applied to numerous situations - specifically hot-button political debates - such as nuclear power, financial regulation, abortion, gun control, privacy, war, cars, computers, cats and dogs.

Although, the main problem is: acknowledging fundamental, incorrigible assumptions that underpin the different world views doesn’t exactly bring any debate closer to resolution. Is there a common rationality to bridge world views?

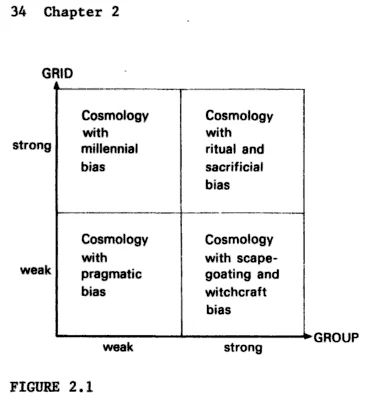

In a 1982, Michael Thompson’s chapter in Essays in the Sociology of Perception presents the diagram connects particular “social contexts” to particular “cosmologies.”

In later adaptions, the four cultural world views were overlaid with four complimentary “myths of nature” which stem from the early work of Michael Thompson as well as another prominent contributors to Cultural Theory: Karl Dake. In the image below, the black line indicates the resilience of the environment, the ball represents the status quo.

The “Individualist” views the environment as incredibly resilient, the status quo can be pushed a great deal without irreversible consequences. The “Hierarchist” thinks the environment is resilient to a point, but resources and actions must be managed carefully to avoid the point of no return. The “Egalitarian” feels the environment (and by extension, the status quo) is incredibly fragile, so we should be careful not to roll the ball much if at all. And, the “Fatalist” thinks there is no rhyme or reason to the environment, and no way of knowing for sure the consequences of our actions.

Now that we have this beautiful, simple heuristic tool, how do we apply it? Are entire nations one culture? Probably not, although Douglas often conceded that the smaller “tribal” societies she studied were largely homogenous in cultural world view. From the United States perspective, it might seem rather easy to apply this model, with some modification, to the various political parties.

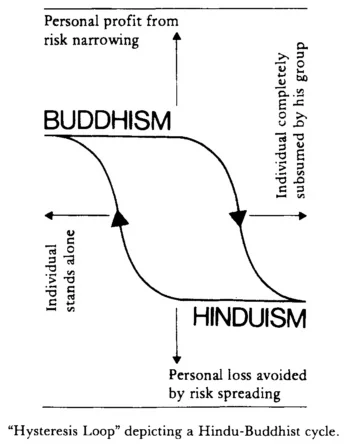

If one nation-state is subdivided into multiple competing world views, can people switch? The answer provided by another Cultural theorist, Michael Thompson, in short, is “yes.” In “Why Climb Everest? A Critique of Risk Assessment,” he describes the cultures of high altitude mountaineers as divided between “Hindus” or “risk avoiders” and “Buddhists” or “risk-takers.”

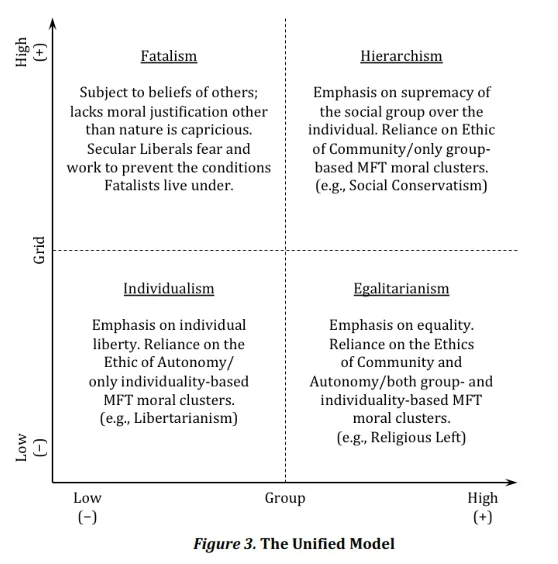

Although, Grid/Group Theory has played less of a role in social theorizing of late, it has not given up the rattle! In a very recent article published in 2013, Joshua Bruce attempts to integrate insights from Grid/Group Theory, with Richard Shweder’s “Big Three” ethics and Jonathan Haidt’s “Moral Foundations Theory” into a unified whole. The following is his result:

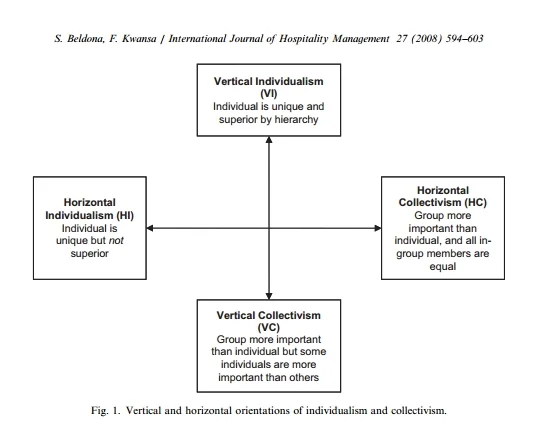

It also appears that Douglas and Wildavsky continue to fuel research even without proper citation. In a 2008 study of fairness in pricing perceptions, the authors Beldona and Kwansa use a measure of “cultural orientation” that is essentially a wholesale copy of the grid/group diagram. Vertical being whether a person is pro-hierarchy, and horizontal being where one falls on the individualist vs collectivist continuum.

And, now, I will bring this discussion of the life of a diagram to a close. Also, checkout Fourcultures.org, a blog devoted to the work of Cultural Theory.

References #

Beldona, S. and Kwansa, F., 2008. The impact of cultural orientation on perceived fairness over demand-based pricing. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 27(4):594-603.

Bernstein, B., 1960. Language and social class. The British journal of sociology, 11(3):271-276.

Bernstein, B. and Henderson, D., 1969. Social class differences in the relevance of language to socialization. Sociology, 3(1):1-20.

Bernstein, B., 1971. Class, Codes and Control. Volume 1: Theoretical Studies Towards a Sociology of Language. Psychology Press

Bernstein, B., 1974. Class, Codes and Control. Volume 2: Applied Studies Towards a Sociology of Language Psychology Press

Bernstein, B., 1975. Class, Codes and Control. Volume 3: Towards a Theory of Educational Transmission. Psychology Press.

Bernstein, B., 1977. Class, Codes and Control. Volume 4: The Structuring of Pedagogic Discourse. Psychology Press.

Bruce, J.R., 2013. Uniting theories of morality, religion, and social interaction: Grid-group cultural theory, the “Big Three” ethics, and moral foundations theory. Psychology & Society, 5(1):37-50.

Douglas, M., 2013 [1963[. The Lele of the Kasai. Routledge.

Douglas, M., 2003 [1966]. Purity and danger: An analysis of concepts of pollution and taboo. Routledge.

Douglas, M., 1970. Natural Symbols: Explorations in Cosmology. Pantheon.

Douglas, M., 2013 [1982]. Essays on the Sociology of Perception. Routledge.

Douglas, M. and Wildavsky, A., 1983. Risk and culture: An essay on the selection of technological and environmental dangers. Univ of California Press.

Oldroyd, D.R., 1986. Grid/Group Analysis for Historians of Science?. History of science, 24(2):145-171.

Rayner, S.F., 1979. The Classification and Dynamics of Sectarian Forms of Organisation: Grid/Group Perspectives on the Far-Left in Britain (Doctoral dissertation, University of London).

Thompson, M., 1983. Why climb Everest? A critique of risk assessment. Mountain Research and Development, pp.299-302.

Thompson, M., Ellis, R. and Wildavsky, A., 1990. Cultural Theory. Routledge.